The year is 2021, and the most-talked-about pop star in the world is Britney Spears. Yes, that’s the same Britney Spears who hasn’t released a studio album since the Obama administration. The same Britney Spears who hasn’t toured since 2018. And the same Britney Spears who, two years ago, announced an “indefinite work hiatus” and canceled a Las Vegas residency weeks before it was scheduled to start. In fact, one way of explaining the resurgence of interest in all things Britney is that she’s now in the news because of how long she’s been out of the news.

Specifically, she is suddenly ubiquitous in pop culture—in headlines, on social media and in multiple SNL sketches—thanks to a new documentary called Framing Britney Spears that is now streaming via FX on Hulu. Directed by Samantha Stark, as part of the series The New York Times Presents, it offers a thorough chronology of Spears’ career from The Mickey Mouse Club through her seemingly isolated present, with a focus on the conservatorship she was placed under in 2008, which gave her father Jamie Spears control over her finances and career. Though it’s not a polemic, the film’s underlying argument is clear. As the legion of fans turned activists who’ve spent years agitating on her behalf so forcefully put it: #FreeBritney.

That rallying cry has spread since the doc’s Feb. 5 premiere, and the movement to liberate the 39-year-old performer and mom is rapidly gaining momentum. Media outlets, as well as comedians like Sarah Silverman, have expressed regret over their treatment of her. Her ex-boyfriend Justin Timberlake—whom Stark singles out for manipulating the narrative around their breakup—apologized to not just Spears, but also Janet Jackson, whose career suffered after he exposed her nipple in a notorious incident at the 2004 Super Bowl. On Feb. 11, a judge confirmed that Jamie Spears would have to share conservatorship duties with a third party, in a partnership that will presumably prevent him from wielding unilateral power over his daughter.

It’s been a heartening, if long overdue, corrective to decades of casual cruelty toward a woman who has openly struggled with sexual objectification, paparazzi surveillance, harsh media scrutiny and mental health. Spears isn’t the only specter of turn-of-the-millennium femininity to become the subject of a massive public reconsideration recently, either. A few days after Framing Britney Spears debuted, Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel actor Charisma Carpenter spoke out about what she called abuses of power on the part of the shows’ creator, Joss Whedon, touching off a new wave of mourning among fans who’ve been hearing reports of vicious behavior on Whedon’s part for years now, and for whom Buffy had long ago become a symbol of empowered femininity.

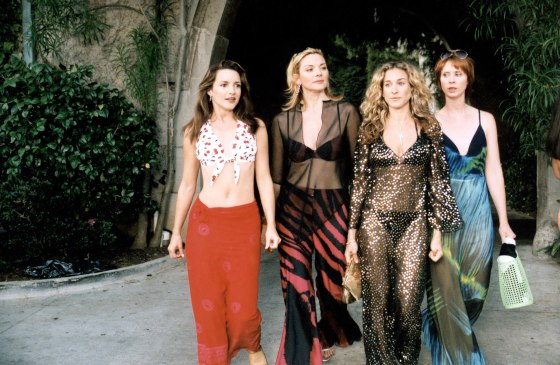

This re-evaluation isn’t likely to end anytime soon. In January, the stars of Sex and the City (minus Kim Cattrall), TV’s most influential depiction of womanhood in the late ‘90s and early ’00s, announced that a revival was in the works for HBO Max. While still a cultural touchstone, the show has grown more controversial since its 2004 finale, as a powerful movement for inclusion in Hollywood casts its very white New York in an increasingly unflattering light and an economy in seemingly permanent post-2008 flux encourages a dimmer view of the characters’ conspicuous consumption.

Whether you attribute them to a 20-year nostalgia cycle, a new wave of feminism or both, these blasts from the recent past add up to a larger reckoning with how pop culture treated women a generation ago. It was an era of unprecedented frankness around female sexuality, influenced by the adversarial but often overlapping zeitgeists of third-wave feminism—which emphasized individualism and sex positivity—and postfeminism, or the presumption that equality had for all practical purposes been achieved.

The good news was that old stigmas around femininity, sex work and the enjoyment of pop culture faded. The bad news? Many women felt pressure to excel at everything—to be fully actualized in their careers and satisfied in their relationships, but also crafty, kitchen-savvy sex goddesses with toned abs and flawless makeup. (Cue Oprah taking the stage to “I’m Every Woman.”) Meanwhile, amid a booming economy, the ecstasy of female purchasing power could drown out scrutiny of what was being sold to women, from thousand-dollar heels and breast implants to snarky supermarket tabloids and teen pop stars in crop tops. And then there was the tendency of the white, middle-class feminist establishment to ignore the millions of women who weren’t in a position to buy their way to fulfillment. In 2021, the gender politics of those so-called postfeminist years can look kind of prehistoric—and so the current reassessment of them is a healthy one. More than just generational infighting, this conversation is a way of deepening our understanding of the past and sharpening our priorities in the present.

Postfeminism and, to a lesser extent, the relatively playful third wave were a gift to the entertainment industry. For the first time in decades, Hollywood could—without looking retrograde—fill its frames with hot girls in tight clothes who lived to shop, primp and have sex. The updated version differed from the Playboy Playmates and housewives of the ’50s in that its ideal femme also, figuratively if not literally, kicked ass. As attractive to women as it was titillating to men, this image sold product.

Romance novels were rebranded as chick lit and followed single career girls with disposable income, like Bridget Jones and “Shopaholic” Becky Bloomwood. On TV and in movies, we got the high-achieving, materialistic women warriors of Sex and the City, but also Ally McBeal, Legally Blonde, the Cameron Diaz canon, and more Bridget Jones. Teen fare like Buffy, Mean Girls and Bring It On offered a junior version of the same: cutthroat high-school girls for whom short skirts and lipstick were weapons of war. In music, the explicitly feminist acts that ruled the early ’90s, from Salt-N-Pepa to TLC to Bikini Kill, begat the sparklier Spice Girls, Britney, Christina Aguilera, Jessica Simpson, Beyoncé’s breakout group Destiny’s Child and a raft of other beautiful young singers who existed at the intersection of strength and sex appeal.

A lot of these stories and personalities were fun. Many served as talismans for female fans in a sexist society. But the public response to them was confusing and incoherent. Did we look up to these women because they were powerful and confident, or because they were pretty and rich—or both? Was it OK that women were contorting themselves, physically and otherwise, to emulate these new quasi-feminist icons? And why did we respond with such schadenfreude when very young, very famous women like Spears, Amy Winehouse or Lindsay Lohan revealed themselves, under the constant glare of flashbulbs, to be less than invincible?

These questions are much older than Framing Britney Spears. Journalist Ariel Levy wrote the first draft in her widely read 2005 book Female Chauvinist Pigs: Women and the Rise of Raunch Culture, which fuses reportage and polemic to argue that the era’s supposedly sex-positive culture was mostly just enlisting women in their own objectification. It’s an important book, but one whose lack of interest in class, race or the systemic roots of women’s choices has not aged well. Feminist consciousness and the cultural conversation at large have shifted in the past 16 years. Social media has given marginalized voices a bigger platform, while intersectionality—the idea that all aspects of a person’s identity combine to form a matrix of privileges and oppressions—has filtered down from academic discourse to the mainstream. Two turning points were Spears’ breakdown in the late aughts and the death of Amy Winehouse in 2011, tragedies that revealed how much damage years of surveillance, objectification and ridicule could do to a young woman. Another was the SlutWalk movement of the early 2010s, which brought women into the streets, often in skimpy outfits, to protest a legal system that blamed rape victims instead of their attackers. When some Black feminists criticized SlutWalk, pointing out that Black women had been treated as sex objects for centuries and didn’t have the luxury of “reclaiming” that identity, a reckoning ensued over the racial politics of sex-positive feminism.

The greatest shift in the conversation around women in pop culture has been the increasingly widespread understanding that to move past postfeminist “raunch culture,” the entertainment industry as a whole—more than the individual “female chauvinist pigs” who have been influenced by it—needs to change. Could the air of straight-male fantasy surrounding Buffy Summers’ heroism, from her low-cut costumes to her habit of jumping into bed with adult men (not to mention centuries-old monsters), have reflected the influence of the same straight man who is now accused of mistreating those women? Didn’t it matter that the stylish, hypersexual and often vapid female characters of Sex and the City, Ally McBeal and their ilk were shaped by male creators? Or that, before the internet opened doors for less traditional teen idols from Lily Allen to Billie Eilish, female pop stars who would ultimately be marketed to young girls had no choice but to run the male-gaze gauntlet that is the music industry?

Two decades on, it seems obvious that a pretty effective way to discourage women’s self-objectification is to liberate women’s bodies, stories and personas from male gatekeepers. Efforts to do just that have taken on a new urgency since the rise of the #MeToo movement in 2017, which punctured the postfeminist fantasy that gender equity and women’s sexual sovereignty were already the norm in the entertainment industry (or any workplace). And over the past decade, although progress has been far from steady and parity has proven elusive, women have slowly increased their presence behind the camera as writers, directors and producers.

More important, for the purposes of this conversation at least, is how many of the most culturally resonant representations of women on film and TV during those years were also conceptualized and helmed by women, from Michaela Coel to Chloé Zhao, Shonda Rhimes to Céline Sciamma. In the gross-out gags of Bridesmaids and Broad City as well as the strip-club revisionism of Hustlers and P-Valley, female creators have challenged the idea that raunchy humor and sexually explicit content must cater to patriarchal tastes. Pop has become the domain of women—Rihanna, Taylor Swift, Lady Gaga, grown-up Beyoncé—with public profiles that resemble early-’90s Madonna more than mid-’00s Britney, keeping tight control over their image by assuming the roles of director, producer, curator, actor and entrepreneur.

As for Spears, it is a very good thing that we are finally talking about the objectification, infantilization, gaslighting, ridicule and invasions of privacy she’s suffered—and about our own complicity in that suffering. But that doesn’t mean we should pat ourselves on the back for finally showing this woman the empathy she has always deserved. Nor should we get too excited about how far we’ve come, as a culture, since the heyday of Perez Hilton and Us Weekly. As many veterans of the movement have noted, the traction feminism has gained within the cultural realm in the last decade has rarely extended to politics, where, for instance, Roe v. Wade is under serious threat, rape still goes mostly unpunished and a disproportionately high number of single mothers live in poverty. If we take just one lesson from Framing Britney Spears, it should be that what passes for progress in one era is bound to look different to the next generation.

0 comentários:

Post a Comment