Jean-Marc Vallée, Director of ‘Dallas Buyers Club,’ Dies at 58

Five Science-Fiction Movies to Stream Now

‘Don’t Look Up’ Review: Tick, Tick, Kablooey

‘The Matrix Resurrections’ Review: Slipping Through Dreamland (Again)

Kevin Feige and Amy Pascal on the Future of ‘Spider-Man’ and the M.C.U.

See the Real Live Man Who Grew Up in a Carnival

Golden Globes Nominations 2022: The Complete List

Best Movies of 2021

Alana Haim Surprised Everyone With Her Movie Debut. Even Herself.

Netflix Holiday Movies Ranked, From Tree Toppers to Lumps of Coal

‘The Power of the Dog’: About That Ending

Alec Baldwin Says He ‘Didn’t Pull the Trigger’ in ‘Rust’ Killing

The Best Thanksgiving Movies to Stream

‘Passing’ Review: Black Skin, White Masks

Benedict Cumberbatch and the Monsters Among Us

A Call of ‘Cold Gun!’ A Live Round. And Death on a Film Set.

Criminal Charges Possible in Shooting on Alec Baldwin Set, D.A. Says

Loose and Boxed Ammunition Found at Scene of Alec Baldwin Shooting

What We Know About the Fatal Shooting on Alec Baldwin’s New Mexico Movie Set

In the Company of Wes Anderson

Selma Blair Wants You to See Her Living With Multiple Sclerosis

Today news: What Happened, Brittany Murphy?, Britney Spears and the Gendered Perils of Child Stardom

Slowly but surely, we’re looking back at the tragic it girls of the aughts and finding out how little we actually knew—or, sadly, cared—about the people they were. Paris Hilton came forward, in last year’s film This Is Paris, with allegations that she was abused as a teenager at a series of residential reform schools—and explained that her airhead-heiress persona was an act devised to achieve financial independence from her family. A devastating court statement and a raft of investigative documentaries have revealed the extent to which Britney Spears has, by many accounts, lived like a prisoner since 2008. Now, the reckoning has expanded to encompass a misunderstood actor who didn’t live to tell her own tale: Brittany Murphy.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

What Happened, Brittany Murphy?, which will arrive on HBO Max on Oct. 14, feels a bit tawdry. Directed by Cynthia Hill (Private Violence), the docuseries, such as it is, consists of two hour-long episodes bridged by a flashy cliffhanger; it could easily have been a feature, but you can’t binge one of those. Unlike This Is Paris or FX and the New York Times’ pair of Spears docs, its balance between respectful reevaluation of its subject and true-crime salaciousness tilts conspicuously toward the latter. When it comes to new insight, What Happened has much more to offer into Murphy’s nightmare husband, Simon Monjack, than into the actor herself. But, taken together with everything we’ve learned about the other Britney these past several months, it does raise some questions about the lifelong perils of child stardom for women in particular.

For those who were too young or too checked out of celebrity culture (lucky you) at the time, Brittany Murphy, who died under mysterious circumstances at just 32 years old, in December 2009, was once among the most endearing young stars in Hollywood. A bubbly New Jersey theater kid raised by a supportive single mom, Sharon Murphy, she was booking commercials and TV appearances by middle school. At 17, she made her film debut as Clueless’ wide-eyed transfer student Tai, memorably wringing every ounce of humor out of the 1995 teen classic’s immoral burn “you’re a virgin who can’t drive.” (“The way she delivers it just gives you chills,” says Clueless director Amy Heckerling in What Happened.) A series of diverse, well-received performances followed, in top-tier movies including Girl, Interrupted (1999) and 8 Mile (2002).

Hill pegs Just Married, a 2003 rom-com in which Murphy starred with her then-boyfriend Ashton Kutcher, as both the peak of her mainstream fame and the beginning of her downfall. A few years earlier, despite being thin by any rational metric and after losing a role amid feedback that she was “cute but not f-ckable,” she had lost a significant amount of weight. Add to that a public breakup with Kutcher—one that sounds ugly but about which, curiously, celebrity interviewees like Murphy’s King of the Hill castmate Kathy Najimy don’t seem to want to say much—and Murphy was in the tabloid-media crosshairs. Accusations of anorexia and drug addiction flew, as well as some slut-shaming for good measure. Cue repentant aughts-era gossip blogger Perez Hilton, now a fixture of docs like this one, to offer some self-flagellation over his old habit of scrawling mean phrases on photos of Murphy in MS Paint.

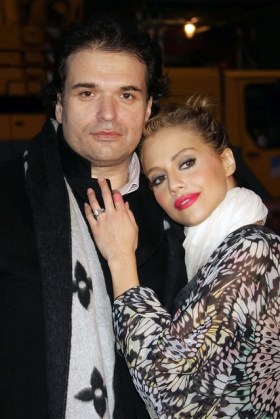

After years of merciless public scrutiny, Murphy met and married Monjack, a screenwriter of little renown. Friends and colleagues repeatedly describe him as controlling. There is talk of his obsession with skeletally skinny women, alleged penchant for doing BDSM-tinged photo shoots with the actor and micromanagement of her appearance; one makeup artist incredulously recounts his insistence on doing her makeup for a role himself. Najimy suspects that he took her phone and kept her away from other modes of communication, because she eventually became fully unreachable—shades of Jamie Spears. Monjack grew so creepily close to Sharon Murphy, who remained a fixture in her daughter’s life, that some suspected, as they tearfully made the media rounds together following Brittany’s death, that they were more than just in-laws. And in the big investigative coup of What Happened, Hill interviews Monjack’s mother and brother, as well as the mother of one his two children (neither of which Murphy seems to have known about).

The revelations about his deceptions are juicy if you’re into scammer stories in the vein of Love Fraud, but Monjack mostly comes off as a garden-variety true-crime psycho who lucked into marrying a movie star. Though Hill revisits several rumors and alternate theories about why Murphy died, including the possibility that she was poisoned, getting to know Monjack doesn’t ultimately change what’s on her death certificate: severe pneumonia, with anemia plus prescription and OTC drugs as contributing factors. It’s also impossible for the filmmaker to confront him or advance a criminal case about his treatment of Murphy and many other people in his life because he died five months after his wife, under weirdly similar circumstances.

Which is only one reason why Monjack’s deceptions turn out to be less compelling than the question of why a person of Murphy’s fame and success could so quickly fall under his sway. For me, the key moment in What’s Happening comes about 20 minutes into the first episode, when Heckerling and others are describing the strange, isolated lives of child actors, for whom an education so often consists of a pile of textbooks skimmed during breaks from work, rather than a classroom full of kids their own age. “You don’t become as aware of people and what they can do—and the petty stuff that people can do, or lies,” Chris Snyder, Murphy’s first agent, reflects. “All that little stuff that you work out in junior high and high school. So that you kind of get caught into this vacuum of not knowing who a good person is and who a bad person is.”

It’s impossible to hear this without making a connection to Spears—who also rose to fame in her mid-teens and who has also been described, like Murphy, as an extraordinarily sweet, open and trusting person. I also thought of Soleil Moon Frye, the Punky Brewster star whose bittersweet Hulu doc kid 90 collects footage from her teenage years, when she underwent breast reduction surgery after earning the cruel nickname “Punky Boobster” and, later, was raped before consensually losing her virginity. It isn’t news that child stars can have difficult transitions to adulthood, with tragic outcomes ranging from substance abuse to suicide, but maybe, even after #MeToo, we haven’t talked enough about the gendered perils of early fame.

Women who grew up in the public eye, like Natalie Portman, Mara Wilson and Raven Symone, have described feeling insecure in their bodies and uncomfortable about their sexuality as a result of receiving so much harsh, judgmental feedback, from the industry as well as the media, about their appearances as kids. Although different people can react differently to the same experiences, it seems likely that such heightened sensitivity to criticism, combined with the loneliness of child stardom, could shape a fragile teenager into an adult who is intensely vulnerable to gaslighting. When your image is simultaneously so public and so far outside your control, what a relief it might be when a forceful, self-assured man comes along to relieve you of the burden of making your own decisions and interacting with the world.

To Hill’s credit, she includes enough serious, observant conversations about Murphy’s work and talents that the series doesn’t register as schlock, exactly. But the emphasis on Monjack, and the suspense with which his backstory is teased, undermines any attempt at high-mindedness. Other weird choices, like the frequent montages of armchair detectives on YouTube puzzling out Murphy’s case while also performing makeup tutorials, suggest a desire to pad out the material to fill two hours. I wish that space had, instead, been used to expand the series’ consideration of why so many young, famous women have found themselves in situations similar to the one surrounding Murphy’s death. As is, What’s Happening, Brittany Murphy? feels like an episode of Inside Edition smoothed out to become a prestige mini-binge. The line between vindicating an unfairly maligned person and continuing to posthumously exploit her has rarely been so thin.

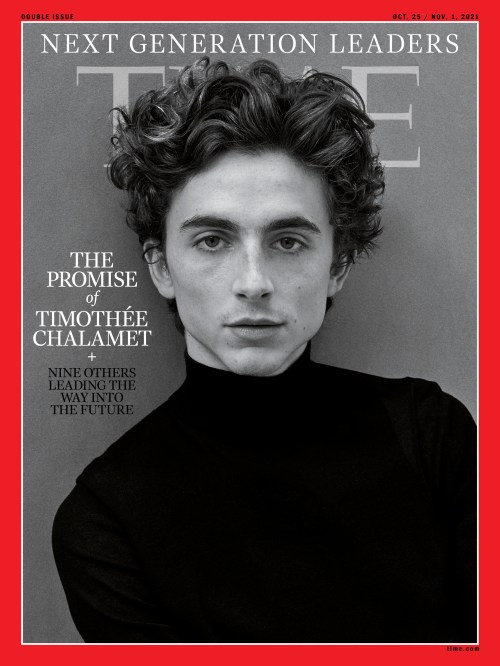

Today news: Timothée Chalamet Wants You to Wear Your Heart on Your Sleeve

Timothée Chalamet and I are on the run, chasing down Sixth Avenue on a bright September day in search of a place to talk. The restaurant in Greenwich Village where we had planned to meet ended up getting swarmed by NYU students while I was waiting for him, chattering excitedly to one another—“Timothée Chalamet is here!” “Shut up!” “Yeah, he’s right outside!”—so, trying to avoid a deluge of selfie seekers, I bolt from the table, tapping Chalamet on the shoulder where he stands under the awning, on the phone, and we make our escape. Face covered with a mask and hoodie pulled up over his curly hair, he’s mostly incognito but still cuts a distinct enough figure that we’d better find a new location fast, and standing at a crosswalk with him, I feel briefly protective, like I should be prepared to body-block an onslaught of fans at any moment.

<strong>“I feel like I’m here to show that to wear your heart on your sleeve is O.K.”</strong>[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Luckily, we go undetected as we make our way to another diner a few blocks down—a true New York greasy spoon, less crowded and doggedly uncool—and slide into a back booth. He orders black coffee and matzo-ball soup, which he says he has been craving. It’s not an easy thing to come by in London, where he’s been in rehearsals for Wonka, an original movie musical that will serve as a prequel of sorts to Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, following the titular chocolatier as a young man. He just spent a weekend recording music for the film at Abbey Road. “I felt out of my league,” he says of working in that legendary space. “Like I was desecrating history!” But working on this project has been good for him. “It’s not mining the darker emotions in life,” he says. “It’s a celebration of being off-center and of being O.K. with the weirder parts of you that don’t quite fit in.”

If Chalamet—whom most people call, affectionately, Timmy—sees himself as off-center, so far it’s working. He’s back in New York for the Met Gala, which he’s co-chairing alongside Billie Eilish, Naomi Osaka and Amanda Gorman. (He walked the red carpet in a Haider Ackermann satin tuxedo jacket and sweatpants.) On Oct. 22, he’ll appear in two films released on the same day. There’s Wes Anderson’s ensemble The French Dispatch, which earned raves out of Cannes, in which Chalamet appears opposite Frances McDormand as a revolutionary spearheading a student liberation movement. He also stars as royal Paul Atreides in Denis Villeneuve’s towering sci-fi epic Dune, an adaptation of Frank Herbert’s beloved 1965 novel, budgeted at a reported $165 million and slated for a massive worldwide release.

This makes it a big moment for Chalamet, who is not just an actor who works often, although he does, and not just a celebrity, although he is one, but a movie star in the old-fashioned sense of the word. (More on this later.) He’s now the rare performer who, at 25, studios are betting can help launch a blockbuster franchise and a festival hit on the same day, with a pandemic still rumbling out of view. With great power, of course, comes great responsibility—including a spotlight on everything from his personal life (he’s been linked to actor Lily-Rose Depp) to his activism (he’s outspoken on climate change) to what he wears, whether on a red carpet or dashing to the bodega. The latter runs the gamut from embroidered joggers to tie-dye overalls to space-age suiting—or, say, a Louis Vuitton hoodie spangled with 3,000 Swarovski crystals. (All this has led GQ to crown him one of the best-dressed men in the world.)

Chalamet belongs to a generation that’s known for oversharing, particularly on social media, but his Instagram is frequently enigmatic; he holds more back than many of his contemporaries. He cites as role models Michael B. Jordan, Leonardo DiCaprio and Jennifer Lawrence—the latter two of whom he’ll appear opposite in Adam McKay’s star-studded Don’t Look Up on Netflix in December—actors who are more likely to talk about craft than to post selfies doing sponsored content. If fame is surreal to him, he also doesn’t make a show of resisting it. “I’m figuring it out,” Chalamet says. “On my worst days, I feel a tension in figuring it out. But on my best days, I feel like I’m growing right on time.”

As we sit and talk, a procession of fans stop by the table to ask for photos—mostly young women, but there’s one sheepish-looking guy, too, who looks to be in his 40s. Chalamet indulges them all gamely, making conversation. “Oh, you go to Columbia?” he says to one girl. “That’s cool! I did too.” He stops himself. “Well, I dropped out.”

If the challenge is staying level amid all this attention, he has a game plan. “One of my heroes—I can’t say who or he’d kick my ass—he put his arm around me the first night we met and gave me some advice,” he says. What was it, I ask?

“No hard drugs,” Chalamet says, “and no superhero movies.”

Chalamet grew up in midtown Manhattan, where his mom was a Broadway performer and his father worked as an editor for UNICEF. He went to the arts high school La Guardia, where he performed onstage. Not long after graduating, he booked a role as Matthew McConaughey’s son in Christopher Nolan’s 2014 space drama Interstellar, which he, along with everyone he knew, expected would catalyze his career. “I remember seeing it and weeping,” he says, “60% because I was so moved by it, and 40% because I’d thought I was in the movie so much more than I am.”

He briefly attended Columbia, then NYU, but didn’t finish college, which he says seems “insane in retrospect.” He remembers the insecurity of those years, which he describes as “the soul-crushing anxiety of feeling like I had a lot to give without any platform.” But he waited for the kinds of jobs he wanted, trying to avoid getting locked into a commitment that might stifle his growth, like a years-long TV contract. “Not that those opportunities were coming at me plenty,” he says, “because they weren’t. But I had a marathon mentality, which is hard when everything is instant gratification.”

That paid off in 2017 with the release of Luca Guadagnino’s gay love story Call Me by Your Name, which earned him an Oscar nomination and catapulted him to fame. (He demurs when asked about co-star Armie Hammer, who has denied a widely publicized accusation of rape. “I totally get why you’re asking that,” he says, “but it’s a question worthy of a larger conversation, and I don’t want to give you a partial response.”) That same year, he featured in Greta Gerwig’s Oscar-nominated Lady Bird. He followed up with the addiction drama Beautiful Boy, then Gerwig’s adaptation of Little Women, both of which earned him still more critical praise.

If his filmography has made him an art-house darling, Dune feels like the perfect big movie for an actor like Chalamet: despite the booming score and dazzling visual effects, there’s a gravity to it—and an unusual prescience. “Dune was written 60 years ago, but its themes hold up today,” Chalamet says. “A warning against the exploitation of the environment, a warning against colonialism, a warning against technology.”

Dune is also the kind of cinematic event that demands to be seen in theaters, which spelled controversy when Warner Bros. announced that, due to the pandemic, all of their 2021 films would premiere on the streaming service HBO Max concurrent with their theatrical release dates. Chalamet shrugs about it. “It’s so above my pay grade,” he says. “Maybe I’m naive, but I trust the powers that be. I’m just grateful it’s coming out at all.”

A day later, we meet at a bar in Tribeca. As he arrives, he’s wrapping up a call. “Love you too, Grandma,” he says gently into the phone as he’s hanging up.

Male movie stars have long been defined by an old model of masculinity. Chalamet, who rose to fame playing a queer character and whose style is frequently described as androgynous, evinces a kind of masculinity that’s a little different: more sensitive, more emotional, in keeping with his generation’s permissive attitudes about self-expression. “Timothée is a thoughtful, poetic spirit,” says Villeneuve. “I am always impressed by his beautiful vulnerability.” Chalamet doesn’t always reveal much, but what he does is intentional. Ask him what he stands for, and he considers it seriously. “I feel like I’m here to show that to wear your heart on your sleeve is O.K.,” he says.

Yet Chalamet knows better than to obsess about how he’s perceived by the public. “To keep the ball rolling creatively takes a certain ignorance to the way you’re consumed,” he says. He calls it a “mirror vacuum”: the black hole you disappear into studying your own reflection. He wants to use his platform thoughtfully, to spread the right kinds of messages through the world—whether that’s about mental-health awareness, a subject which he wants to see become “less of an Instagram slide share and something more intrinsic,” or climate. “I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the same generation that inherits the overheated planet is the generation saying, ‘Hey, there’s a level of complacency here,’” he says.

All that said, Chalamet doesn’t take himself too seriously. The idea that he’s seen as a movie star—let alone his generation’s most promising—seems to make him squirrelly. “I don’t want to say some vapid, self-effacing thing,” he says. “It’s a combination of luck and getting good advice early in my career not to pigeonhole myself.” The term movie star, to him, is “like death.” All it does is make him think about ’90s-nostalgia Instagram feeds.

“You’re just an actor,” Chalamet says, like a mantra. “You’re just an actor!” Then he looks to me, as if checking to see if he’s convinced me it’s true.

Cover styled by Erin Walsh; grooming by Jamie Taylor

Today news: How No Time to Die’s Unprecedented Ending Sets Up the Future of the Bond Franchise

Warning: Major spoilers for No Time to Die ahead.

Bond is dead. Long live James Bond.

In the franchise’s storied 58-year history, 007 has never actually died. Bond movies usually end with the successful destruction of a villain’s lair, and the camera panning away as the hero beds a Bond girl—on a boat, in space, on a balcony, often with his would-be rescuers looking on. The next movie may star the same actor or a different one, but rarely does anything of real consequence—romances, villainous encounters—carry over from film to film. Even when Bond’s wife was murdered on their wedding day in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969), she’s never even mentioned in the film’s sequel, Diamonds Are Forever (1971). Even when Bond hunts down Blofeld, the man he presumably holds responsible for his wife’s death, he never even mentions Tracy’s name.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

That refusal to establish Bond film continuity changed in a big way with Casino Royale (2006), the first to star Daniel Craig in its title role. That film ends with the revelation that Bond’s first true love, Vesper, was being blackmailed by a villainous figure. At their behest, she worked to entrap Bond but later sacrificed her life in order to save his. In the final scene of Casino Royale, Bond begins his journey to discovering the man responsible for Vesper’s betrayal and death, and subsequent movies follow him down the rabbit hole of exposing the evil organization Spectre and its leader, Ernst Blofeld (Christoph Waltz). In 2015’s Spectre, 007 finally finds Blofeld and learns that this man was in fact the “architect” of all of Bond’s pain throughout the entire movie series. Everything is connected, alas.

And so No Time to Die, released in theaters Oct. 8, endeavors to bring this arc to a close with an actual finale. And, despite the movie’s title, James Bond—as played by Craig in his last outing as the famous spy—does, in fact, die. Here’s why 007 had to sacrifice himself and what it means for the future of the franchise.

Read More: No Time to Die Is an Imperfect Movie. But It’s a Perfect Finale for the Best James Bond Ever

How James Bond dies

The path to Bond’s demise starts with the movie’s first major twist, another departure for the famously unattached spy. Halfway through the film, Bond discovers that he has a daughter. It’s a first for any 007.

At the beginning of the movie, Bond finds himself deeply in love with Madeleine Swann (Léa Seydoux), whom he met during the events of Spectre. Swann says that in order for the two of them to have a future together, Bond needs to let go of the memory of Vesper. Bond visits Vesper’s grave in Italy, only for the tomb to explode in an attempted assassination by Spectre goons.

Bond, of course, escapes the explosion relatively unscathed only to be greeted by the aforementioned goons. During a fight scene, one such thug insinuates that Madeleine betrayed him—just like Vesper had. A wounded Bond kills the bad guys and puts Madeleine on a train, planning to never see her again. He then heads to a remote island to live out his retirement in teeny, tiny swim trunks.

Five years later, Bond is dragged back into the spy game and collides with none other than Madeleine, who is now working as a therapist for MI6. And, surprise! She has a daughter. (MI6 apparently did not know about this child, which makes one seriously question the abilities of the Brits to gather intelligence. A dozen megalomaniacs have vendettas against Bond at this point. Maybe they should keep better track of his possible offspring, who would be obvious targets for kidnapping?)

Madeleine claims the child is not Bond’s. It’s a pretty obvious lie. As Bond points out, they share the same intense blue eyes. Madeleine will, of course, later in the movie confess that his suspicions are well-founded. Predictably, the movie’s villain, Safin (Rami Malek) kidnaps Madeleine and the child and takes them to his lair, an island where he harvests a bunch of different poisons because, well, he’s a creepy Bond villain.

Safin is mass-producing a bioweapon, a poison that is programmed to people’s specific DNA. If the targeted person is exposed to that poison, they will die, even though the carrier of the toxin will remain unharmed. He wants to use the poisons to target specific people and throw the world into chaos for vague bad-guy reasons.

With the help of another 00 agent, Nomi (Lashana Lynch), Bond gets Madeleine and their daughter off the island. Bond stays behind to open a bunch of missile silos so that the Brits can blow the place to smithereens, only to encounter Safin on his way out. Safin poisons Bond with a toxin that will specifically kill Madeleine and their daughter if Bond goes anywhere near them, which means Bond can never touch his love or child ever again. Tech genius Q (Ben Whishaw) tells Bond that there’s no way to remove the toxin once it’s been applied. How he can possibly know this—and whether some experimentation over the course of years could lead to a cure—is unclear, but Bond accepts this fate quickly.

Bond shoots Safin dead, and then calls Madeleine to wish her farewell as he watches several missiles approach the island. And then, boom, Bond is gone. Whether you’re a fan of Daniel Craig’s portrayal of Bond or not, it’s a rather poetic ending to the era. The five films that starred him successfully pivoted the franchise from one-off romps filled with fast cars, cool gadgets and, yes, the Bond woman, to a brutal epic of a hitman trying to find his soul.

But Bond’s death was also necessary for this franchise to survive.

Was a permanent end necessary to let Daniel Craig finally bow out?

It’s no secret that Daniel Craig has wanted out from the Bond franchise for awhile now. He infamously declared in 2015 he’d rather “slash his wrists” than return the character and quipped that if he did come back it would only be for money. He did, of course, end up coming back for one more outing. One can’t help but speculate that he returned to the franchise on the condition that he be offed by the end of the film so a massive paycheck could never tempt him again.

He’s not the first actor to want out of an iconic role. Harrison Ford reportedly begged George Lucas to kill Han Solo before finally getting his wish at the hands of J.J. Abrams, decades later, in The Force Awakens. Leonard Nimoy reportedly wanted to kill off Spock in Wrath of Khan only to later change his mind. Even Sean Connery, the man who made James Bond an icon, wanted 007 dead after playing the character seven times (though he never got his wish). Onscreen deaths can not only offer an actor a reprieve from a role that offers diminishing creative returns, but a heroic and bittersweet demise can also engender sympathy for a character and cement their cinematic legacy.

Craig craved an identity beyond the Bond character. Thankfully, he has found it in other films, particularly as Detective Benoit Blanc in Knives Out, which is getting a whole series of movies on Netflix. Now, unless the Bond Cinematic Universe goes the way of superhero films and begins resurrecting characters using time travel, quantum mechanics and whatever other movie magic the writers can think up, he’ll be able to move on from Bond forever.

Bond’s sacrifice gives him a redemptive arc that modern audiences need

We all know that the character of James Bond is problematic. The character has a history of raping, objectifying and using women. And Bond movies often glamorized that behavior. The character taught generations of men that misogyny was cool. Just as little girls look to figures like Barbie to perceive what they should be, what they should value and how they should interact with men when they grow up, so too do little boys look for cues from famous, enduring figures like Bond.

To its credit, Casino Royale tried to reckon with the question of how, exactly, Bond became such a misogynist. A betrayal by a woman provided part of the answer, though misogyny seemed to be baked into Bond’s very character. Before Craig’s Bond ever meets Vesper, he sleeps with a woman for information and is hardly perturbed when he finds her brutally murdered the next day. By the end of the movie, when he finds out that Vesper both betrayed and saved him, he responds, infamously, “The bitch is dead.”

It’s hard to reconcile that brutal perspective with the fact that Bond remained eminently hip—a familiar vehicle through which tailors and car dealers and watchmakers could hawk their wares to an adoring public. The movie wanted us to acknowledge this man we idolized was a monster, but didn’t want us to stop idolizing him.

How, exactly, that character could survive a post-#MeToo era was unclear. Could the world’s most famous fictional misogynist endure? Would he have to reform?

Given the choice between reckoning with Bond’s past and ignoring it, No Time to Die—the first Bond movie filmed since #MeToo went viral in 2017—leans into the latter. Nomi, who bears the title of 007 herself for much of the film, occasionally quips that Bond is a dinosaur. But by the end of the movie, she cedes the 007 title to him as a sign of respect, seemingly offering her approval and erasing any of his past misdeeds.

How does Bond go from questionable womanizer to good guy so quickly? The answer lies squarely at the feet of his daughter. As soon as she enters the picture, the most brutal things Bond does, like dropping a car on a bad guy begging for his life, are not out of coldness but in service of this innocent. The audience automatically extends sympathy to a man just trying to defend his family. He is, to use a phrase that has been wielded (and mocked) widely in recent years, now the forever awakened father of a daughter.

This isn’t a new trick in Hollywood. Dads looking to protect, specifically, their young girls have been in vogue as of late: Just look at Taken, Stillwater, Sweet Girl and, in the closest parallel to the current Bond plot, Avengers: Endgame.

Read more: From Stillwater to Sweet Girl, A New Crop of Movies Explores the Plight of Modern Dads

Hollywood has a knack for redeeming womanizers

This redemption arc is a familiar one. Only two years after Casino Royale premiered, Iron Man debuted, launching the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU). The movie improbably starred the world’s biggest playboy as a superhero. Like Bond, Robert Downey Jr.’s Tony Stark engaged in some womanizing that has aged particularly poorly, including sleeping with a journalist that Stark’s assistant, Pepper Potts, deems “trash,” and ogling bikini pictures of Scarlett Johansson’s Black Widow, whom Pepper observes is “a very expensive potential sexual harassment suit.” (The fact that Gwyneth Paltrow as Pepper Potts had to utter both of these putdowns of fellow women is particularly gross.)

But by the time that (spoiler alert for Avengers: Endgame) Tony Stark sacrificed himself at the end of that saga, he was—you guessed it—the father of an adorable little girl, an all-around family man and unassailable hero. Both franchises had years to get with the times, to transform IP created for another era (Bond and Iron Man were conceived in 1953 and 1963, respectively) into the sorts of protagonists we can actually applaud today.

In fact, No Time to Die and Avengers: Endgame bear striking parallels. Bond and Stark are both anti-heroes who do questionable things for the sake of humanity, even if Bond puts a grimmer spin on his actions than the smirking Tony Stark. Each reforms, retires and seemingly finds his happily-ever-afters off the beaten path—Bond gleefully whispers “Je t’aime” to Madeleine as they tumble into bed at an Italian hotel together at the beginning of No Time to Die; Stark, meanwhile, feeds his daughter ice pops in the woods as they tell each other, “I love you 3000.”

A plea to return to the fray arrives from a friend, Felix Lighter in Bond’s case and Steve Rogers in Stark’s. Each agrees, in part because of guilt. (Stark gazes at a picture of the disappeared Peter Parker he failed to save, Bond tells Madeleine his greatest regret is putting her on that train.) After a touching scene with their mini-mes—Stark’s daughter dons the Iron Man helmet, while Bond’s daughter blinks up at him with his bright blue eyes—they sacrifice themselves for the greater good.

With that, the redemption arc that might win over even the most skeptical audience members is complete. And it offers a clean slate to whoever might come next.

Where does the Bond franchise go from here?

Does Bond’s death (and the fact that it so heavily evokes the sacrifice of a superhero) suggest that we’re about to get the Marvelization of Bond? That might seem antithetical to the franchise, which has always casually recast new actors to play the role without ever commenting on it in the film. Bond exists outside of time and space, never explicitly aging and always evolving to suit the needs of a new era.

The Craig era of Bond movies has strayed from that ethos a bit. This Bond did, indeed, grow old and now has met his demise. Many 007 fans booed Spectre exactly because it got so bogged down in the mythology of the franchise, tracing which old villains came from where and obsessing over the hero’s origin story rather than cool cards and well-cut suits. If Bond has gained gravity, even gained a soul, he’s lost the lightness of those first films. Until now, the Bond films could be watched in a vacuum or as part of a binge, and even the silliest ones satisfied because of just how ridiculous and disposable everything and everyone in them was, including not only the Bond girls but also the hero himself, subbed out every few years. In such a grim offscreen moment, fans would be forgiven for longing for that carefree version of the character.

But is Bond’s misogyny so coded into his DNA that it’s impossible to remake this character? Craig’s Bond bore women ill feelings, and the series reckoned with them only slightly before offering him a saving grace in the form of a daughter. Would another, lighter version simply make light of the fact that this character has existed in the public imagination as an chauvinist for all this time?

It’s hard to imagine it would. It wasn’t 007 slapping girls in the face that made those older Bond movies enjoyable. It was the lightness with which he handled even the most terrifying villain’s plots, meeting them with a quip and a swig of his martini.

The producers have said they won’t begin their hunt for the next Bond until next year. And though the introduction of Nomi suggested Lynch might inherit the role, producers and Craig have shut those rumors down. Craig recently said that he didn’t think Bond should be a woman. “Why should a woman play James Bond when there should be a part just as good as James Bond, but for a woman?”

While that might be the ideal circumstance, that suggestion ignores the fact that nobody (save, perhaps, Christopher Nolan) can seem to get an original idea greenlit in Hollywood these days. Studios are obsessed with IP and old, proven IP, especially in the domain of action and spy thrillers, simply does not exist for women. Searching for a history of female spies, all one can find is Charlie’s Angels, whose gender politics are so fraught to that story of three women at the beck and call of a mysterious man may be impossible to adapt well. The most promising female spy movie may in fact be a spinoff from the Bond franchise, perhaps one set in Cuba and starring Ana de Armas, the breakout star of No Time to Die (and Craig’s co-star in Knives Out).

But certainly, now that Craig has put his Bond to bed, the Broccoli family has an opportunity to signal to the world that they are rethinking this character, dragging him into the modern era if they must. They can reshape him or confront his past. But they cannot outrun his legacy.

Today news: Meg Cabot Won’t Give Up on Happy Endings

The drinking game goes like this: every time you mention COVID-19, take a sip. It’s six minutes into my conversation with Meg Cabot when she makes the rules. We’re sharing margaritas over Zoom to discuss topics like fictional feuding authors, rom-coms and the magnificent Julie Andrews. But, as it always seems to go these days, asking an innocuous question like “How long have you lived in Florida?” soon gives way to an aside about case counts and shutdowns—and we can’t have that, Cabot suggests, because we are here to have fun.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

I remember the 12-year-old version of myself, practicing my curtsy in case it ever turned out that I, too, was a long-lost royal like Mia Thermopolis, née Amelia Mignonette Grimaldi Thermopolis Renaldo, Princess of Genovia. I can’t let that middle schooler down. I lift my drink in the air. This is Meg. Freaking. Cabot. We’re going to have a good time.

Are you also one of the readers for whom Cabot’s books served as a guiding force through the turbulent years of adolescence? I know you’re out there, because Cabot, 54, has sold over 25 million copies of her more than 80 books for children, teens and adults. Among her lengthy backlist—filled with coming-of-age stories centering fiery heroines and enemies-to-lovers romances—are her smash hit Mediator and Princess Diaries series. The former is set to be adapted by Netflix. The latter, which began with the story of a teenage girl living through bad hair days and unrequited crushes in New York City only to discover she’s actually the princess of a small European country, was the inspiration for two Disney movies in the early 2000s. Those films grossed over $300 million, featured Anne Hathaway’s big-screen debut (not to mention one of the most iconic makeover scenes of the past 25 years) and served as an entry into reading for countless young people who saw the movies, picked up the books and never looked back. “To me, that’s the greatest thing,” Cabot says. “I love that there are movies that turn people into readers.” And the fandom has endured, fueled by spin-offs about Mia’s little sister, an adult book that follows Mia later in life, occasional tweets that Cabot posts in the voice of her heroine and rumors about a third film. Cabot keeps it brief when asked about a possible new movie. “We don’t want to risk Julie Andrews’ life with COVID,” she says. “Let’s take a drink!”

Statement from Princess Mia Thermopolis of Genovia: Wishing #MeghanAndHarry all the best. PS The royal guest house here at the palace is always available for you.

— Meg Cabot (@megcabot) January 8, 2020

Though Cabot is best known for her contributions to the young-adult landscape, she first entered the literary scene writing historical romances for adults. Over the years, her focus has rarely remained on a single age category. “If I had to do just one, I would get so bored,” she says. Her adult books appeal to readers looking for over-the-top, propulsive plots and laugh-out-loud humor. The Boy Next Door, from 2002, explores the relationship between a gossip columnist and a man pretending to be her neighbor’s nephew, through a narrative written entirely in emails. Size 12 Is Not Fat, which kicked off Cabot’s Heather Wells Mysteries series in 2006, centers on a former pop icon who, after being dropped by her label for gaining weight, works at a college where a student is found dead in an elevator shaft. More recently, her Little Bridge Island series, all romances set in the Florida Keys, have offered respite from the outside world—sparking, as NPR put in a review of the first installment, “readers’ hope for humanity.”

Now, the author is preparing to release her 28th adult novel on Oct. 12. No Words, the third Little Bridge Island book, follows Jo Wright, a successful children’s author, at a book festival where she just so happens to run into her arch nemesis Will Price, a pretentious adult novelist. Jo despises Will for dismissing her in a past interview, and is certain that he looks down on her for writing about the adventures of a fictional kitten. At the festival, the two bicker, disagree and are thrown into so many of the same panels, cocktail hours and parties it seems like they just can’t escape each other. And did I mention he’s very handsome?

You know how this story ends. That’s exactly why you picked up a Cabot book. In a world that feels increasingly dreary by the day, we can count on her delightful narratives to distract and entertain. “I want to be the author who provides somebody in emotional distress with comfort,” Cabot says firmly. “And the comfort that I want to provide is a hopeful or happy ending.”

There’s a reason for her obsession with tidy resolutions. Growing up in Indiana in the 1970s, Cabot was a reluctant reader. It wasn’t until she saw the 1966 movie Fantastic Voyage—and later read Isaac Asimov’s novelization of its screenplay—that things changed. The book was one of the first she read from start to finish, propelled by her ability to visualize the scenes. Amid a tough childhood marked by difficult periods with her father, who was an alcoholic, reading became a means of escape.

But when Cabot was 13 years old, she was burned by a book. After starting to watch a PBS TV adaptation of George Eliot’s 1860 classic The Mill on the Floss, a coming-of-age story about first love, she picked up the book. Fascinated by protagonist Maggie Tulliver, she sped ahead of the show and was devastated that the narrative took a tragic turn. “She freaking dies!” says Cabot, still smarting more than 40 years later. After the Mill on the Floss debacle, Cabot vowed always to read the ending of a book before diving in, as a defensive measure. To this day, she still picks her reads with happy endings in mind, often returning to writers she trusts to give her what she wants.

Read More: The 100 Best YA Books of All Time

By the same token, it’s important to Cabot to shield her readers from the pain of a tragic resolution—for young readers in particular, she remembers what it was like to be a teenage girl, and it was hard enough without being knocked sideways by a book. While sad literary fiction abounded when she was a teen, Cabot struggled to find hopeful books about young women she could relate to, save for the works of Paula Danziger and Judy Blume.

These days, YA literature offers no shortage of options for readers, and Cabot herself is part of the reason. She set an example with her protagonists who think and feel like actual teenagers. The Princess Diaries’ Mia was a staunch vegetarian who rocked Doc Martens and thought a lot about French kissing. That series’ influence on the category is indelible: YA books have long been marketed as “the next Princess Diaries,” and still are 21 years after its first installment. Hester Browne’s The Runaway Princess, from 2012: “The Princess Diaries meets Runaway Bride.” Rachel Hawkins’ Prince Charming, from 2019: a “Princess Diaries turned-upside-down story.” This year’s Tokyo Ever After, by Emiko Jean: “Princess Diaries meets Crazy Rich Asians.”

But Cabot’s success did not always come easy. The Princess Diaries was rejected countless times. “Not just rejected,” she says. “People were mad. I got rejections from people who said this was not suitable for children—or anyone.” The book’s references to sex and body parts and instances of cursing and underage drinking were, somehow, shocking to people when she took it to market in the late 90s. Cabot felt like the industry was not ready to accept narratives about girls that didn’t involve moral lessons. “There was a feeling at that time that entertaining books, just pure entertainment for teenage girls, was not a thing,” she says.

The idea of pure entertainment is not quite accurate to what Cabot writes, she concedes. She grounds all her work, not just her YA novels, in a slightly sweeter version of our world—one where characters still face, but always overcome, some ugly aspects of life. In No Words, Cabot made a point to touch on sexist power dynamics in the publishing industry through the story of a secondary character taking advantage of a young fan at the festival—a dark thread that ties the ultimately cheery book to reality. “My book is like 100 pounds of sugar with a little dose of medicine in it,” she says.

We’re drinking again because I’ve asked Cabot where she got the idea for the new book, and she explains it was born out of her feeling sad that literary festivals were canceled last year due to the pandemic. She wrote No Words at home in Florida during lockdown (take a sip!) and entirely outdoors. In the bleary, distracting days of the past year or so (another sip!), she had to completely disconnect from the Internet in order to write, and the only place to do that was outside, where she worked on a portable, battery-powered word processor—sometimes while floating on a raft in her pool.

Readers might wonder if the prolific-author protagonist of No Words is based on Cabot herself. She is quick to deny that Jo is her carbon copy, but they do have a few things in common. They both are writers with a talent for revisiting the same characters over and over again, to great success. Jo is working on the 27th installment of her Kitty Katz series while Cabot has written 14 series, including 24 installments of The Princess Diaries, eight installments of the Mediator books and six installments of Allie Finkle’s Rules for Girls.

And both women share a flair for the romantic. But they follow the rule books of very different rom-coms. Jo’s journey to love is fueled by anger and resentment—feelings that she is forced to second-guess after she learns that Will might not be such a bad guy. Cabot is living out a quirkier love story: she and her husband, who she met when she was 16 years old, eloped in Italy on April Fool’s Day, 1993, because they thought it would be funny. The mayor of the town almost refused to officiate because he thought they weren’t taking their marriage seriously, and Cabot is still not entirely sure their marriage is legal—their names are spelled wrong on their license. “We’ve been together almost 30 years,” she says, smiling, “so hopefully it’s real!”

But here’s where Cabot truly differs from her latest protagonist: While No Words’ Jo gets snappy when fans express to her that they “used” to love her books, for Cabot, that kind of feedback never gets old. She tells me about a time she went to a restaurant after giving a talk at a school and being sent dessert from a table of eighth-grade girls. Now that her fans are older, she says, gesturing my way, they send over drinks. She looks right at me. “My readers are growing up.”

Sign up for More to the Story, TIME’s weekly entertainment newsletter, to get the context you need for the pop culture you love